Carbon footprint calculators have been on my radar for a long time now, and lately ‘Net Zero’ has crept into the frame. Having followed green-living news out of interest, it’s inevitable; I could hardly have missed either of these terms. I’ve tried plugging my life details into a few carbon footprint calculators, out of curiosity, but now, I think differently about them, so dare I ask – should we ditch carbon footprint calculators; and carbon credit scores? Do they reflect the real world well, and is there an agenda behind them? Even if they’re not on your radar, it may be worth taking a look.

I question carbon footprints because I think they show our obsession with screwing life down to one element, and, to numbers. This might apply more, though, to the people who design carbon footprint calculators in the first place. Maybe we (everyday people) just accept them and think they must be right? It’s not just because I’ve never been good at maths that I mistrust an over-reliance on numbers – it’s because it’s easy to pull the wool over peoples’ eyes with scores and percentages; to convince us of just about anything by expressing life in abstract terms.

‘Tread Lightly on the Earth’, They Say

They seem like a good idea because in an era of plenty, we don’t tend to take stock of the resources we use, and neither are we naturally in a position where we have no choice but to live frugally. And, by frugal, I don’t mean a life of dull denial; just living more with what we need. Most people feel they need some guidance on how to do this, and carbon footprint calculators seem like a good guide. I assume, if you’re reading this, that it’s something you think about.

We probably think that by using a carbon footprint calculator, someone has done the work for us (so convenient). But, we might gain from doing the work ourselves, asking what was that new bag made from? What went into growing the food in our shopping bags, and how far did it travel to get there? With our fridge freezers, washing machines, dishwashers and TVs whirring away in the background, how much energy is it all taking? I suspect, most of us don’t know, and think that we need to know exactly. And, that means numbers.

I don’t mean to send you on a guilt trip – we have enough to think about, after all. But, if you enter into the world of carbon footprint calculators, someone’s counting… Who?

Who Are the Number Crunchers?

And here’s the thing. Do we ever ask, how the number crunchers made their calculations? Who punched the numbers? What assumptions did they make in order to rate, or grade, our scores? Would they give us a green badge, or rate us as an eco failure? If we don’t know who punched the numbers, we could be outsourcing our thinking. Even if you would never go near a carbon footprint calculator, people in powerful positions are using these for you, then feeding the results into general political decisions in ways you might not realise.

They’re counting carbon: an important part of nearly everything we use – but these carbon calculators usually mostly represent carbon dioxide emissions (related to the goods or services we use): chosen because carbon dioxide is considered a greenhouse gas. We’re in a phase of global warming because of greenhouse gases, or so we hear. Are we? That’s a question for another time.

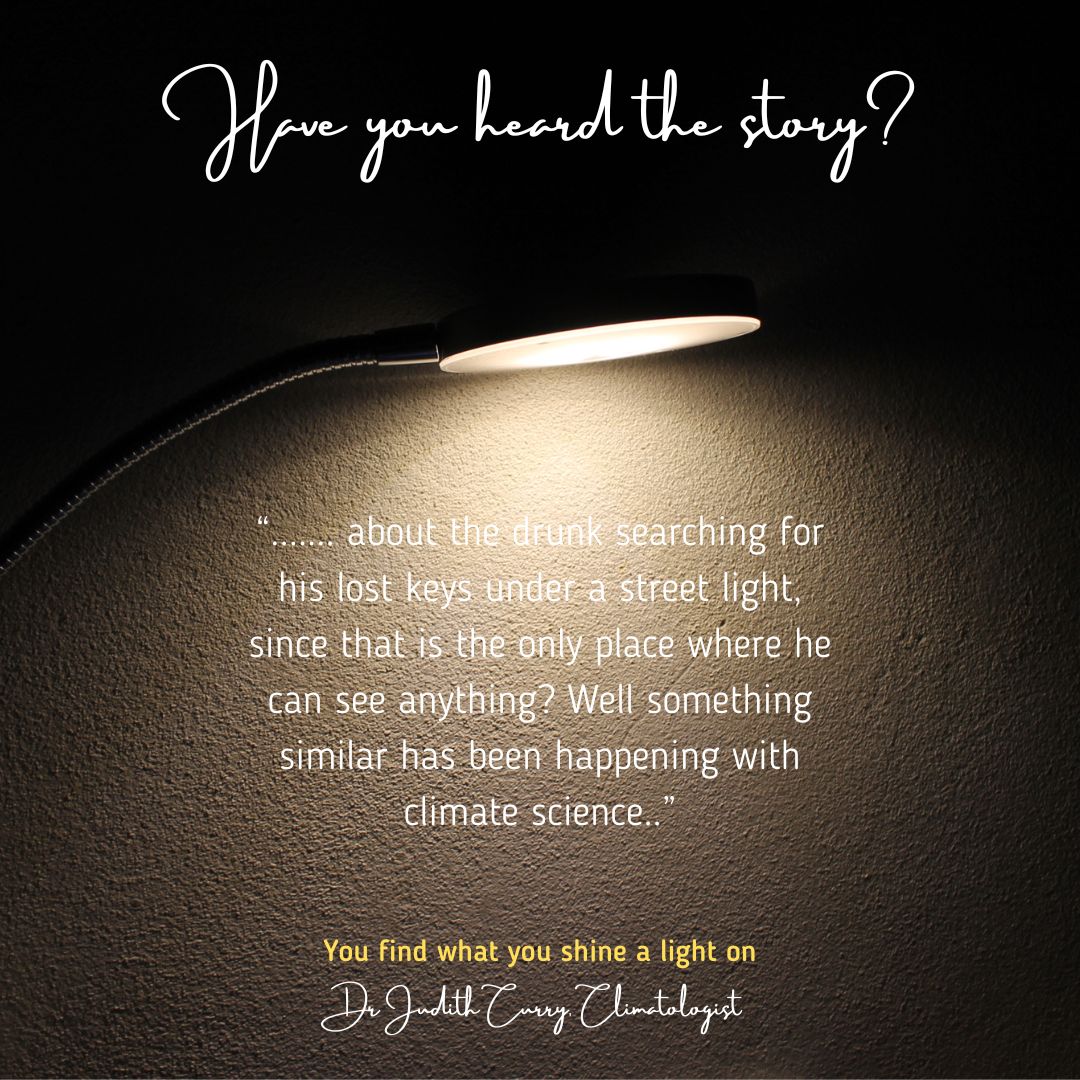

This gas (CO2) makes up just 0.04% of earth’s atmosphere. We hear that our contribution to the 0.04% is anywhere from 0.03% to ‘very difficult to predict’. Climatologist, Judith Curry states this in many of her blogs on Climate etc, and her new book, Climate Uncertainty and Risk: Rethinking Our Response, which is attracting some attention.

You Find What You Shine a Light On

So, is this a good way to think about our life footprint? Curry makes use of a story about a drunk man searching for his keys under a street light, since that’s the only place where he can see anything. The point is, she says, that you find what you shine a light on, and something similar has been happening with climate change. Carbon footprint calulators and carbon credit scores then repeat this single focus. Are we (or society) getting too single-focused?

Are Carbon Footprint Calculators Right About Cows?

Carbon footprint calculators often give good hints, that once prompted most of us would realise are quite self-evident. I’m unlikely to disagree with scoring well for buying second hand, recycling, mending and repurposing. It’s been a way of life for me for as long as I can remember. And, for most people, it’s not hard to understand why being a little more frugal in this way would be better for us, and the world around us.

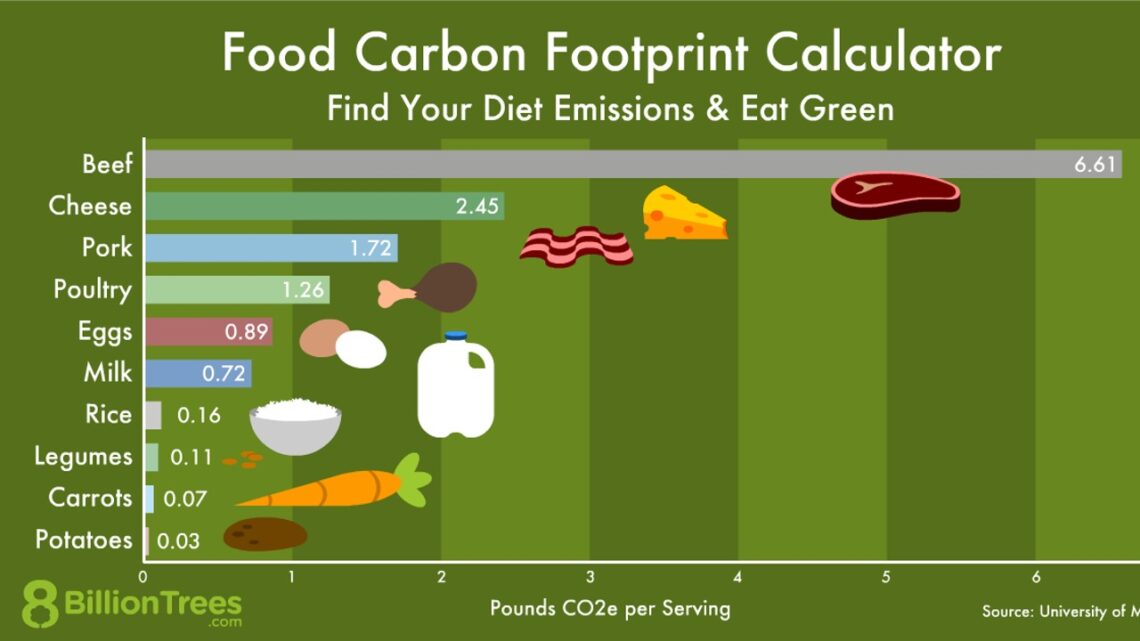

But, what if you see punchy images showing kilograms of methane (considered a greenhouse gas) that cows burp out into the atmosphere, produced for every kilogram of beef? Or, of pounds of CO2 per serving of a food type? Would you believe that livestock are destroying the planet?

This concept is so simply and attractively presented. When we’re bombarded with this type of information, it’s easy to find our perception of cows, placidly grazing on pasture, taking a rightful place in our farmed landscape obliterated. Cheese becomes, not natural produce from a pastoral landscape, but a carbon dioxide emitter. Rice and avocados (imported from where?) would make us a more saintly eater. ‘Follow the science’, they say, and we rarely question.

As I say in my book, ‘Eat Like Your Ancestors‘, about the current focus on statistics:

‘… where are the words about the farmers who grow our food? Of animals, pasture and cornfield – the stuff of our childhood learn-to-read books? We can find them, but other voices speak louder.‘

Large swathes of landscape have been pastoral for aeons, and farmers are telling us why. Cows, sheep, goats and pigs have been with us for a long time, for good reason.

Ask a Farmer Instead of Reading a Graph

Apart from asking simple questions (rightly raised by carbon footprint calculators). like ‘How local is my food’, ‘Could I go organic?’, we could go deeper. Choose one subject, and go deeper.

We could ask a farmer, or many farmers, because they don’t all think and farm in the same way. Most of us, though, aren’t in a position to stroll up to a farmer and start asking questions. We can, instead, read their words and listen to them speak; for they are speaking up. James Rebanks, a Lake District Farmer has attracted an audience with his English Pastoral: An Inheritance. John Lewis Stempel, a Herefordshire farmer (in my neck of the woods) has written many popular farming-themed books. My favourite is The Running Hare: The Secret Life of Farmland. Sarah Langford writes about her journey towards regenerative farming when she took over a farm, in Rooted: How Regenerative Farming Can Change the World. For those who prefer to listen, James Rebanks has been speaking on podcasts, for instance ‘In Conversation With James Rebanks‘ on The Sustainable Food Trust podcast.

These farmers give me a sense of the power of place. Graphs portraying statistics speak of nowhere food, disconnecting me from the real world. We can find it hard to judge how to act when life is presented to us in an abstract way. Check out my book (Eat Like Your Ancestors) for some handy tips to eat better and save the planet.

Credit Score World

We’re on our way to a Credit Score World. A Swedish company, Doconomy, has produced a credit card that measures your carbon footprint, and sets monthly CO2 limits. They aim to cut your carbon footprint by 50%. “…it will literally deny cardholders from spending once they have used up their allowance. (Every purchase has a carbon footprint attached, which is displayed on the Doconomy app)”. Is this the future, and would you agree with it?

It would only work if everything you spend is tracked. I mentioned, in a post ‘Alternative Economy, Meaningful Work and Autonomy‘ how the Chinese have been trialling a social credit score system that tracks everything you spend and do to determine your social credit score. It is, I think meant to become obligatory, and it could make it over here.

Nonetheless, numbers, attached to our lifestyle, may increasingly matter, unless we decide otherwise. If we could choose, what could be an alternative way?

Be a Lifelong Learner

If we reject calculators and scores, how do we decide what to do (assuming this is our concern)? We could feel in a fog about it all, but this is because we’ve become de-skilled in many areas of life. We outsource so much to institutions, the state, and those who we believe are the experts. Few people grow their own food, make clothes, or the many goods we rely on. Seeing as so much of what we rely on is becoming electronic or digital, it’s also getting harder to make or repair the goods we use – unless we go analogue.

We can be lifelong learners though, and think for ourselves. Working out our own life footprint takes work, but it’s interesting work.

I make what I can, but where I don’t have time, I try to buy at least a few goods from a single maker or a family firm. We also buy much of our food from a local farmshop, where we find pasture-raised meat, free range eggs from chickens raised on the farm, and veg from fields down the road. We keep our food shopping simple, so it keeps costs down – and we grow some of our own. Every little helps, as they say; a saying ironically now taken over by a large UK corporate supermarket. But, we can take that saying back.

Wildlife In Your Life Footprint

Perhaps we could include wildlife in our life footprints? It’s not just about our own lives (the resources we use), but all life.

Rooks nest high in trees overlooking a field that grew the wheat that made our bread. Birds flit around woodland that produced logs for our woodburner. Worms, critters in the soil, flowering herbs, and even orchids, occupy land that might have housed humongous distribution warehouses, had we not bought more regionally-made goods (there’s a thought). Those making these goods can only stay in business if we buy from them.

We could factor into the equation the life that plants and animals had because of the way our goods were made. We’re hearing more frequently now about regenerative farming, but check out my post on regenerative goods for ideas on how the goods in your life could help all life. Maybe we could have a wildlife index, but, be careful who controls the numbers.

Numbers or Nuanced Understanding?

I’m not completely against numbers and metrics, just because I’m not much of a numbers person myself (that would be very biased). After all politicians will inevitably use them to make decisions. As an example, the Sustainable Food Trust in Britain are part of a move towards a Global Farm Metric to monitor farm sustainability, and I think this metric is meant to make its way onto food produce. I listen to their podcasts and I like their approach, but this will be a global venture with some very big players. We need transparency about the ‘who’ and the assumptions behind any index like this.

But, for us everyday people, we might want to do our own thinking. With lifelong learning comes more nuanced understanding, and the habit of finding out for ourselves what it took to produce those goods – it becomes like muscle memory. Those who take care over what they produce nearly always provide us with the information we need too. Once we find one good source of information, it often points the way to others.

I do believe, it’s information and understanding that most of us need, more than numbers.

If you liked this post, take a look at my book about sustainable food. It’s centred on a journey around where I live, but it’s relevant anywhere. And, it’s out now.