Charcuterie in the pantry or larder. That’s what charcuterie has always been made for. For thousands of years we’ve been dry-curing and smoking meat (before we could import food from all around the world) because we needed to keep going in lean times. And lean times they were, as we had to produce from the landscape outside our door.

Crops won’t grow all year round in cool, rainy Britain, where I live. It’s cooling down already and feels autumn-like right now, despite a long run of very hot summer days. We’ll have winter vegetables on our allotment for a while and then we’ll hit the hungry gap.

The Hungry Gap

I’ve been thinking about traditional food storage – fridge freezer free, and particularly the cured or matured versions of more perishable food. This spring, my husband, Andy, and myself really noticed that hungry gap.

We’d done well with planting up our allotment. Empty shop shelves early in lockdown sure were a big incentive, but we were a little anxious about whether everything would take. After all, we had no idea what would happen to food supplies. Farm shops were producing well, and we didn’t know at the time that their food supply would hold up so well compared to supermarkets.

With the odd lone, withered leek and some sprouting broccoli going over, our allotment looked quite bare. Despite the newly planted rows, harvesting was sometime away.

How did people manage in the past, I wondered?

Would their larders have been lacking? I’ve used two words pantry and larder, but there’s a difference. Think pantry – dry, longterm storage; larder – cooler storage for more perishable foods. Our cupboard under the stairs now performs both functions.

New British Charcuterie

Salami sausages and air-dried hams hang in a whitewashed cool room; the mottled white bloom on the salamis matching the whitewashed walls. All parts of the animal have been used. Nothing is wasted. Salt draws water out of the meat, and along with air drying, it can improve in flavour over several months, or even years.

These are drier cured meats than we’re used to in the UK today. Home cured, with low food miles, from rare breed pigs or wild venison – they’re infiltrating delicatessens over here. There’s a rise in British charcuterie happening, and it’s real food in the raw.

These meat curers tend to raise, or use meat from, rare breed pigs such as Tamworths, Berkshires, and Gloucester Old Spots. These guys take longer to reach maturity, like to live outdoors, and aren’t suited to modern intensive pig farms. Their fattier, drier meat suits salami-type meats better too. It’s not only a liking for this type of food; people want to support more animal-friendly and wildlife-friendly farming.

In our house, we buy most of our meat from local farms, where cattle and sheep graze and trample, and pigs root up the soils for much of the year. One local farm shop has started smoking and dry-curing their own meat. So, we can buy more continental style meat: dry, spicy and easily stored on the cold slab in our pantry mentioned in traditional food storage, for as long as it takes to eat it. We now have charcuterie in the pantry.

Charcuterie in the Pantry: Cure and Mature Your Own

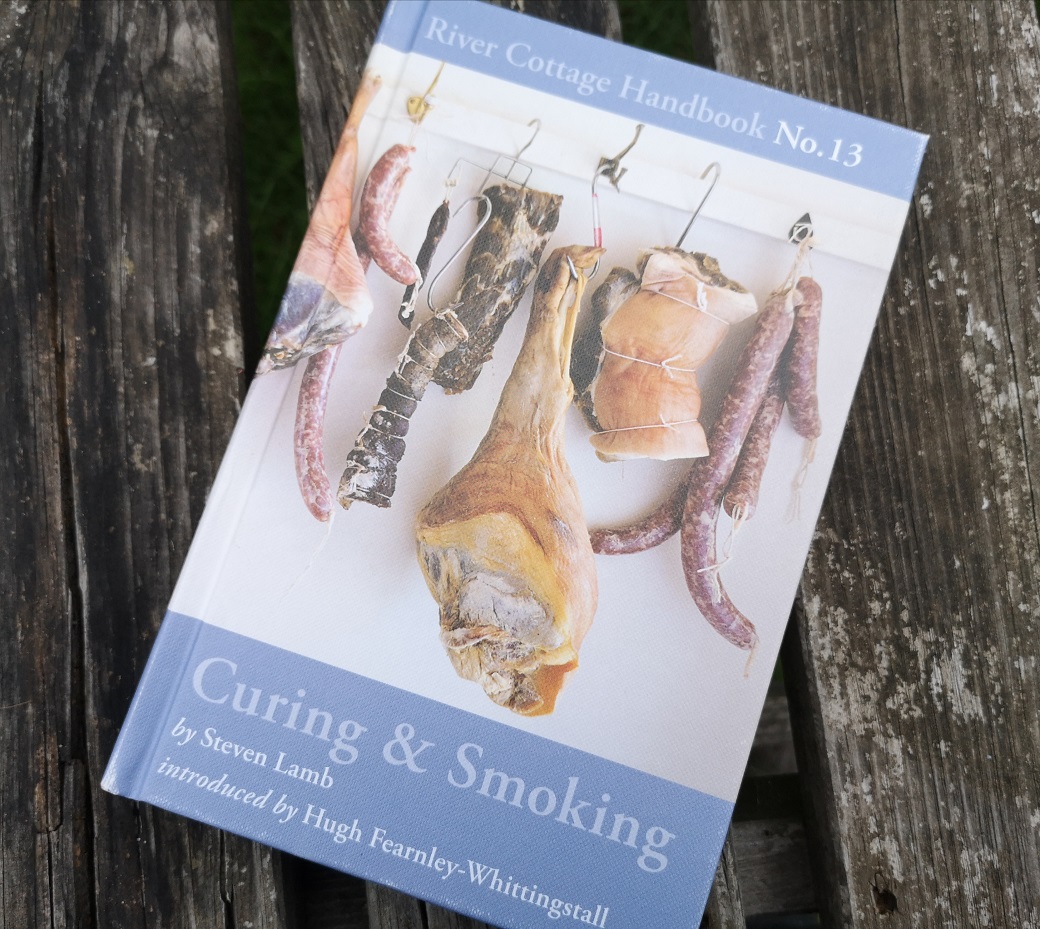

I’ve just bought this book on Curing and Smoking: hot on the heals of my husband buying the Cheese and Dairy companion in the series. I’d like to think that we’ll try our own preserving cheese and dairy, and dry-curing meat. I also have the classic Dorothy Hartley’s Food in England: A Complete Guide to the Food That Makes Us Who We Are. She describes traditional ways of curing hams and beef. If seamen carried food like this on ships, for long sea journeys, it surely must survive in our under stairs larder. This is just one of the ways that we can revive traditional knowledge and add to our skills.

The crew of the 16th century warship, the Mary Rose, lived on a diet of ship’s biscuits, salt beef, butter and cheese. They didn’t get very far out of port, but had they done so, they would have been well-fed!

Pigs and Piglets on Sand in Staffordshire

The local farm shop I’ve mentioned (with the smokery) raises their own grass-fed beef and lamb, but buys in free-range pork from a farm in Staffordshire, one county north of us. This is the home of the Tamworth pig, one of our oldest registered pig breeds. They’re close to the original European forest swine – see them here at the National Trust Shugborough Estate and at Old Hall Rare Breeds.

The Staffordshire farm is in an area where, for many years, archaeologists have dug up residues of past life that lie beneath the soil, in advance of quarrying. It’s a most important area for sand and gravel quarrying.

The Tamworths may only have been known since Sir Robert Peel registered the breed in the mid-1800s. But pigs, generally, would have been in the mix here for a very long time. If we sweep back in time to the middle ages, we’d see pigs, cows, and sheep out in the fields. Many fields of rye too, rotated with beans and peas.

All are important, but particularly pasture, which binds the loose sandy soil together and holds in water. Manure from grazing animals beefs up the nutrients in less than perfect soil. When a field of pasture is ploughed up, it’s most likely to be sown with rye or mixed grains. Rye, with its dense, long roots, hangs on to water and nutrients in the sandy soil. Stretching back into the past, people have farmed this way, with crops and animals closely connected.

Walk onto that land, stripped of topsoil before the quarry machinery moves in, and what you can see is sand, sand, and more sand. Look further south to another quarry at Meriden near Solihull, on the borders of Warwickshire. In Animals and Ancestors: A Life Lived With Animals, I described this landscape, and the people and animals that depended on it. What do we see? More sand.

There are vast tracks of sand running through the west midlands. Find out more about this farmscape in my book, out now. See Eat Like Your Ancestors (From the Ground Beneath Your Feet): A Sustainable Food Journey Around the English West Midlands.

I travel around this sandy part of Staffordshire in Cow and Corn: a preview of Chapter 3 in this book. I’d dropped down from hillier ground, where my husband grew up on a small family farm in Red Rock Farm: Food From the Hills.

Charcuterie on Rye

A little charcuterie in the pantry. What do we eat it with? Slice it up, saw up a homemade loaf of rye bread; add in some pickles, in honour of the Staffordshire countryside we’ve just visited.

This is real, traditional food with authentic taste. The world, though, is changing. We can eat this, or a vast array of food lining the supermarket shelves. You could soon choose a 3-d printed steak. I’d prefer the charcuterie on rye. What would you prefer?

Featured image by Jez Timms on Unsplash.com

I hope I’ve encouraged you to want to Eat Like Your Ancestors. That’s the title of my book, centered on a journey around where I live, but it’s relevant anywhere. It’s out now…